2003 Sanctuary Records

First of all, The Power To Believe, released in 2003, contains, hands down, my least favorite King Crimson song. Happy With What You Have To Be Happy With is noise without relief and lyrical silliness unmatched in the entire catalogue. And the more I listen to this album, the less I like this song. In the absence of everything else, it’s simply annoying. Belew’s just messing around with words in a way that’s less successful than other such messes. It was okay when it was new, with Elephant Talk. Less so, twenty years on. Another reason Happy rubs me raw is that most of the rest of this album is really intriguing. Eyes Wide Open is one of KC’s most beautiful songs, up there with Matte Kudesai and Cadence and Cascade.

The instrumentals Level V (aka Larks’ Tongues In Aspic, Part V), Dangerous Curves, and Elektrik see Crimson addressing the tour de force they specialize in with some of their greatest vigor. Elektrik takes several turns through the quiet-loud arpeggiation cycle that the KC classic sound relies on, with bits of keyboard thrown in.

Dangerous Curves has this building crescendo, starting with a quiet keyboard line that pulls in first drums and then bass and guitar, the drum fills increasing in volume, almost like a bolero. Like the best Crimson pieces, you want to think it’s one thing and then it hypnotically turns into something else, before returning and showing you that it was never the thing you thought at all.

The Belew lyric Facts of Life, which closed out side A is another false start on this album. (Does one even know if this album was sequenced for LP release? Not I.) It’s musically interesting, but lyrically weak. The foolish aphorisms that don’t lead anywhere lead us to believe that Belew was just noodling some more, while giving the illusion of some kind of profundity. ‘Like Abraham and Ishmael fighting over sand/Doesn’t mean you should, just because you can/That is a fact of life…Nobody knows what happens when you die/Believe what you want, it doesn’t mean you’re right/That is a fact of life.’ I think the conclusion the lyrics draw in each verse isn’t supported by the arguments – at a poetic level, it would be more satisfying if he’d left the title phrase out of the sung lyric.

The Belew lyric Facts of Life, which closed out side A is another false start on this album. (Does one even know if this album was sequenced for LP release? Not I.) It’s musically interesting, but lyrically weak. The foolish aphorisms that don’t lead anywhere lead us to believe that Belew was just noodling some more, while giving the illusion of some kind of profundity. ‘Like Abraham and Ishmael fighting over sand/Doesn’t mean you should, just because you can/That is a fact of life…Nobody knows what happens when you die/Believe what you want, it doesn’t mean you’re right/That is a fact of life.’ I think the conclusion the lyrics draw in each verse isn’t supported by the arguments – at a poetic level, it would be more satisfying if he’d left the title phrase out of the sung lyric.

The title track, shared out in four parts, is the most intriguing thing on the album. Part I introduces the album with Belew reciting the text through a vocoder with no accompaniment:

She carries me through days of apathy

She washes over me

She saved my life in a manner of speaking

When she gave me back the power to believe.

Part II opens side 2 as a light percussion/keyboard wash to which bass and guitar later join. The lyrics are the same, still treated, but handled almost as a mantra, a meditation guided by the instrumentation.

Parts III and IV follow Happy and close the album. In part III, the melody and lyrics are pulled apart and given an almost industrial texture, which is interrupted by the classic Robert Fripp lead guitar. Subtitled ‘The Deception of the Thrush’ (a title which shows up on the Level Five EP which preceded this album’s release), those two or three minutes of Fripp taking over might be the most satisfying thing on the album, especially for fans of the classic mid-70s sound.

So, yeah, it’s a whole lot of really good dragged down by two not very interesting songs. And, listen, King Crimson is my favorite band. Those two songs, if they showed up on a Belew Power Trio album, or just about anywhere else, would probably have me hopping gleefully up and down. In the context of an otherwise serious and intellectually engaging album, they get on my nerves. This is still a four-star album, which may give some idea of how the rest of it grabs me. (Note: There’s a tasty new reissue of this one too and it’s on the wishlist in my head.)

I’ve been challenged to review the catalogue of Gentle Giant, a band I’ve only recently been introduced to and about which I know very little. Watch this space.

The instrumental B’Boom follows. After a short introduction, percussionists Bruford and Mastelotto go head to head. This is the first time KC had had two percussionists since that brief period around the recording of Larks’ Tongues In Aspic and this kind of interplay in Crimson got lost again after this album until Fripp regrouped with three drummers in the front line. The song, at least in its title, brings us back to a long improv performed on the LTIA Tour at the Zoom Club called Z’Zoom. (Note that the Zoom Club gig also included two more improvisations: Zoom and Zoom Zoom which together run for over an hour. The band might be referring back to them in the tracks Vrooom and Vrooom Vrooom. I might have to delve back into that recording.)

The instrumental B’Boom follows. After a short introduction, percussionists Bruford and Mastelotto go head to head. This is the first time KC had had two percussionists since that brief period around the recording of Larks’ Tongues In Aspic and this kind of interplay in Crimson got lost again after this album until Fripp regrouped with three drummers in the front line. The song, at least in its title, brings us back to a long improv performed on the LTIA Tour at the Zoom Club called Z’Zoom. (Note that the Zoom Club gig also included two more improvisations: Zoom and Zoom Zoom which together run for over an hour. The band might be referring back to them in the tracks Vrooom and Vrooom Vrooom. I might have to delve back into that recording.) Where the Dark and the Light Mingle concludes with Richard Buckner’s Desire, in which our narrator is done with their last partner, having said too much and too drunkenly, ‘shot my insides out with grief and Mr. Kessler’ and just needs to hit the road. Fed up with life and death and lust and addiction, the road beckons.

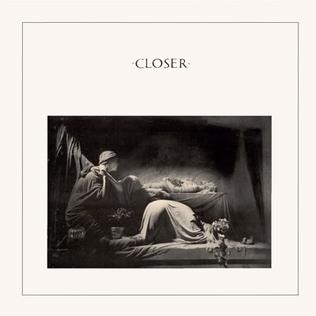

Where the Dark and the Light Mingle concludes with Richard Buckner’s Desire, in which our narrator is done with their last partner, having said too much and too drunkenly, ‘shot my insides out with grief and Mr. Kessler’ and just needs to hit the road. Fed up with life and death and lust and addiction, the road beckons. about Closer, and JD in general for me at the time – I knew a little of the history – I’d even seen New Order (the band formed out of the remains of Joy Division) perform. That would have been in

about Closer, and JD in general for me at the time – I knew a little of the history – I’d even seen New Order (the band formed out of the remains of Joy Division) perform. That would have been in  The fascination for Balance in this movie possibly included what was essentially a music video inserted in the midst of Chas’s mushroom trip. When Jagger

The fascination for Balance in this movie possibly included what was essentially a music video inserted in the midst of Chas’s mushroom trip. When Jagger