This past weekend included a listen to Joy Division’s Substance (1988) and continued reading of bassist Peter Hook’s Joy Division memoir Unknown Pleasures. I first heard Joy Division in 1987 when I went out record shopping with my friend Natalie. She and I had a lot of overlapping tastes, but she was a proper goth and I was just into the music. I knew a lot of Joy Division-adjacent stuff, but hadn’t heard anything by them. She recommended their second album, Closer. I was 20, living in San Francisco, and (as I would for several years) spent a lot of my time not processing my father’s death the previous year. I was hard to reach and generally hard to communicate with. The thing  about Closer, and JD in general for me at the time – I knew a little of the history – I’d even seen New Order (the band formed out of the remains of Joy Division) perform. That would have been in 1985 at the Santa Monica Civic – hadn’t heard any of their music prior and the show was boring – listening to live recordings from that period now – yeah, they were a dull live act). I recall playing this album a lot that year, and feeling all kinds of despair associated with it, primarily because I knew of the untimely death of lead singer Ian Curtis. One of my flatmates at the time told me it was familiar and asked if he would have heard something else by the band. It’s possible, I probably told him, but this tastes and mine were quite different. Yeah, I listened intently to Closer, but I didn’t know (yet) their biggest hit, Love Will Tear Us Apart, which was a little weird. But this was before someone could send you an email saying ‘you’ll like this song’ and before you even read the next sentence, you could be listening to the song.

about Closer, and JD in general for me at the time – I knew a little of the history – I’d even seen New Order (the band formed out of the remains of Joy Division) perform. That would have been in 1985 at the Santa Monica Civic – hadn’t heard any of their music prior and the show was boring – listening to live recordings from that period now – yeah, they were a dull live act). I recall playing this album a lot that year, and feeling all kinds of despair associated with it, primarily because I knew of the untimely death of lead singer Ian Curtis. One of my flatmates at the time told me it was familiar and asked if he would have heard something else by the band. It’s possible, I probably told him, but this tastes and mine were quite different. Yeah, I listened intently to Closer, but I didn’t know (yet) their biggest hit, Love Will Tear Us Apart, which was a little weird. But this was before someone could send you an email saying ‘you’ll like this song’ and before you even read the next sentence, you could be listening to the song.

So, yeah, Lawrence probably had heard Joy Division before me, though hipster that I was, I was loath to admit it.

Anyway, Closer threw me into a funk that was hard to escape but I was compelled to listen to it more and more. I bought Substance the following year and found that I especially liked the post-punk stuff (Atmosphere, Love, Dead Souls, These Days), but really didn’t know what to make of the earlier, punkier tracks. Later I’d buy the Short Circuit compilation (which includes At a Later Date recorded when they were still a punk band called Warsaw) on the same day I purchased Iggy and the Stooges’ Metallic KO. The following week, a friend told me the apocryphal tale of Ian Curtis committing suicide on the eve of Joy Division’s first American tour because he believed they’d never make a record as good as Metallic KO. A cursory search indicates that Curtis played Iggy Pop’s The Idiot and watched a Herzog film before taking his own life at the age of 23. His epilepsy wasn’t a secret to those nearest him, though in the late 70s, people didn’t know so well how to be supportive of an epileptic friend.

Hook notes that everything Joy Division recorded was classic – something he credits to band chemistry, youth, and Curtis’ lyrical brilliance. With this in mind, I can probably say that everything JD recorded , especially after An Ideal For Living, supersedes everything on Metallic KO (much as that document of two late shows from the original incarnation of the Stooges, including their last show in 1974, is brilliant in its own twisted way). Whether JD’s work supersedes The Idiot, well that’s a bit subjective.

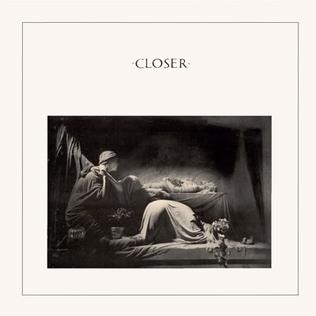

Later I would have a huge poster of the cover of Closer on my wall, next to a huge poster of the cover of Aladdin Sane. As usual, there’s no real conclusion to this story. Even the fact that I’m reading Hook’s memoir right now is a little random. I purchased it for the kindle months ago when it was probably on offer for 99p, about what it cost to see Joy Division open for the Buzzcocks in 1979. It simply came up when I was scrolling through to find what next to read.

Opening with four vocal tracks, none of which (on the face of it) is that demanding on the listener. Title track/opener, Three of a Perfect Pair is an interesting one because it stayed in King Crimson/Crimson ProjeKct set lists well into the 21st century, and as a fan, it’s easy to find that it’s just a little overplayed. Belew is right to be impressed with his ability to play the guitar in one time signature and sing in another, but it’s only because he’s the vocalist that this makes him unique in the band. The song itself being about the breakdown of a relationship seems an apt one as this incarnation of KC was on the verge of collapse at the end of the Beat sessions (and after the tour for this album, these four would not reconvene for 10 years).

Opening with four vocal tracks, none of which (on the face of it) is that demanding on the listener. Title track/opener, Three of a Perfect Pair is an interesting one because it stayed in King Crimson/Crimson ProjeKct set lists well into the 21st century, and as a fan, it’s easy to find that it’s just a little overplayed. Belew is right to be impressed with his ability to play the guitar in one time signature and sing in another, but it’s only because he’s the vocalist that this makes him unique in the band. The song itself being about the breakdown of a relationship seems an apt one as this incarnation of KC was on the verge of collapse at the end of the Beat sessions (and after the tour for this album, these four would not reconvene for 10 years). Side one closes out with Waiting Man, another distinctive Belew vocal which like the title track of the follow-up album seems to have the vocals in one time signature against instrumentation in another. Bill Bruford’s drumming on this piece (as with a lot of the percussion in this period of KC history) seems to owe a bit to Steve Reich’s phase works such as 1971’s

Side one closes out with Waiting Man, another distinctive Belew vocal which like the title track of the follow-up album seems to have the vocals in one time signature against instrumentation in another. Bill Bruford’s drumming on this piece (as with a lot of the percussion in this period of KC history) seems to owe a bit to Steve Reich’s phase works such as 1971’s  Discipline runs the gamut from essentially downtown New York new wave to strangely beautiful downtempo work. Some pieces harken tot the noise mastered by the mid-70s line-up. What’s most interesting about this album (and its two successors) is that Fripp for the first time had a guitar foil in the band who was an equally forceful player. Belew also acted as frontman in a way the earlier singers (including Wetton and Lake) hadn’t. Belew never subsumed his vocal quirkiness to any greater KC ethos. This is also the first album with a co-producer from outside the band. Rhett Davies had recent credits with the second Talking Heads album, Dire Straits’ debut, and multiple Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry albums. It’s possible that he enforced on the band a certain rigid approach, despite what I’m about to say next.

Discipline runs the gamut from essentially downtown New York new wave to strangely beautiful downtempo work. Some pieces harken tot the noise mastered by the mid-70s line-up. What’s most interesting about this album (and its two successors) is that Fripp for the first time had a guitar foil in the band who was an equally forceful player. Belew also acted as frontman in a way the earlier singers (including Wetton and Lake) hadn’t. Belew never subsumed his vocal quirkiness to any greater KC ethos. This is also the first album with a co-producer from outside the band. Rhett Davies had recent credits with the second Talking Heads album, Dire Straits’ debut, and multiple Roxy Music and Bryan Ferry albums. It’s possible that he enforced on the band a certain rigid approach, despite what I’m about to say next. Lyrically, side one has more of the depth found in their earlier work. I can’t really tell if they arranged the tracks for LP release or CD, but major releases still came out on vinyl at the time. After Nighttown, side two has the disco 1-2-3 of the title track, Big Fun, and the aforementioned KC and the Sunshine Band cover. Big Fun has big horns and lyrics about going out and (long before Daft Punk) getting lucky. The chorus of Well-e-o, well-e-o here we go / We got a bite like a pit bull yeah we don’t let go / Well-e-o, well-e-o under the sun / Everybody looking for…big fun doesn’t really suggest the seriousness of purpose the band was known for. On the other hand, the bass and the brass are used to good effect. Even considering the lyrical silliness of Big Fun, the only real embarrassment of the album is the rap that Andrews injects into Get Down Tonight. (All one can say is that it was a thing at the time.)

Lyrically, side one has more of the depth found in their earlier work. I can’t really tell if they arranged the tracks for LP release or CD, but major releases still came out on vinyl at the time. After Nighttown, side two has the disco 1-2-3 of the title track, Big Fun, and the aforementioned KC and the Sunshine Band cover. Big Fun has big horns and lyrics about going out and (long before Daft Punk) getting lucky. The chorus of Well-e-o, well-e-o here we go / We got a bite like a pit bull yeah we don’t let go / Well-e-o, well-e-o under the sun / Everybody looking for…big fun doesn’t really suggest the seriousness of purpose the band was known for. On the other hand, the bass and the brass are used to good effect. Even considering the lyrical silliness of Big Fun, the only real embarrassment of the album is the rap that Andrews injects into Get Down Tonight. (All one can say is that it was a thing at the time.)