And Nothing Hurt – 2018

Oh, man. Have you heard the new Spiritualized album? Dang.

My opinion is that it’s the best work Jason Pierce has done since about 2003’s Amazing Grace. Mind you, the peak is still 1997’s Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating in Space. If our scale is 1-10, then Ladies and Gentlemen is a sold flawless 10 (a 14 or 15 in comparison to even the best albums out there, just not in terms of this band). That’s the gauge. Let it Come Down from 2001 and Amazing Grace come in at 8 or 9. The goal with the latter was to pull away from the excesses of the previous two. (Let It Come Down, for example, took four years and 115 musicians to record.)

2008’s Songs in A&E was recorded in the aftermath of Pierce’s near-death experience with pneumonia and respiratory failure, though mostly written before that. 2012’s Sweet Heart Sweet Light was mostly written on medication for liver disease and suffers, oddly, from both lyrical and arrangement-related excesses. Even still, these are both solid 7s on my Spiritualized scale.

But both are, in my opinion, fairly tame. The new album, however, nails all the best things about Spiritualized in one gorgeous package.

Now, this is the thing about Spiritualized – They (Pierce and whoever he ropes in when he’s ready to work) do a crazy amalgamation of soft balladry, krautrock-inspired drone, psychedelic space rock, and straight-up rock and roll. Sometimes in one song, but usually over the course of an album. And they’re not the only band that takes this kitchen sink approach – but they may be the only one these days to do it so successfully. They’re sort of like the Grateful Dead – the only band to put all these disparate pieces of rock and roll history together and make it work. Anyway, And Nothing Hurt is the return to form I’ve been waiting for. From the ambivalent sweetness of A Perfect Miracle through the nearly eight-minute rampage of The Morning After, to the gospel closing of Sail On Through. Thematically, there’s love, lust, abandonment, road tripping, and suicide, but what’s most touching is the combination of themes in single songs. A Perfect Miracle and I’m Your Man both combine the desire to love and be the best partner with admissions of both past and future failure threaded through. ‘I could be faithful, honest and true…but if you want wasted loaded, permanently folded…I’m your man.’

Now, this is the thing about Spiritualized – They (Pierce and whoever he ropes in when he’s ready to work) do a crazy amalgamation of soft balladry, krautrock-inspired drone, psychedelic space rock, and straight-up rock and roll. Sometimes in one song, but usually over the course of an album. And they’re not the only band that takes this kitchen sink approach – but they may be the only one these days to do it so successfully. They’re sort of like the Grateful Dead – the only band to put all these disparate pieces of rock and roll history together and make it work. Anyway, And Nothing Hurt is the return to form I’ve been waiting for. From the ambivalent sweetness of A Perfect Miracle through the nearly eight-minute rampage of The Morning After, to the gospel closing of Sail On Through. Thematically, there’s love, lust, abandonment, road tripping, and suicide, but what’s most touching is the combination of themes in single songs. A Perfect Miracle and I’m Your Man both combine the desire to love and be the best partner with admissions of both past and future failure threaded through. ‘I could be faithful, honest and true…but if you want wasted loaded, permanently folded…I’m your man.’

Here It Comes (The Road) Let’s Go sounds from the title and the opening twist of an AM radio knob like it should be a tale of an actual road trip, but it’s simply directions to a partner to drive ‘a couple of hours’ to visit where ‘we’ll get stoned all through the night’. Looking about on YouTube, it seems this song dates from the Sweet Heart Sweet Light tour on which it was performed in pretty much the same arrangement. Musically, it’s probably my favourite song on the album.

Let’s Dance builds from a slow piano figure as the narrator tries to convince a girl to dance as the bar they’re in is closing up, ‘The hour is getting late / They’re putting all the chairs away’, but ‘if they’ve got Big Star on the radio, they’ll let us stay’. Gotta love a Big Star reference. And this is another one that’s been gestating for a while. There’s a little viewed live video from 2013 with somewhat different lyrics.

And with On the Sunshine, the album kicks into a higher gear. Yeah, it’s another drug song (‘you can always fix tomorrow what you can’t pull off today’) but powered by organs and horns and without much of a bridge, it just barrels into your ears as sweet as can be.

And then Pierce pulls it all back with the lullaby Damaged. Lyrically, it’s Pierce’s narrator (again – this is a theme across many Spiritualized albums) laying the blame for his unhappiness on a lover who’s left, ‘Darlin’ I’m lost and I’m damaged / Over you,’ but the combination of piano, strings, and fuzzed guitar behind Pierce’s sadness bring all his pain to the fore.

But, then there’s the rocker, The Morning After. Of course, the rock and roll is subverted by the lyrical subject, another Jane (see Sweet Heart Sweet Light’s Hey Jane, for example) who decides her parents are the problem and decides to ‘hang herself up by the bathing pool’. Musically, it kicks right in with a Velvet Underground riff, to which a horn section is added and by the song’s midpoint, it’s moving into free jazz territory.

The album closes with two more slow pieces, The Prize and Sail on Through. The first of these is a lovely waltz in which our hero addresses his love over and over saying I don’t know if I should stay or go or if it’s too late to say goodbye. As is often the case, the objective listener is pretty sure the narrator isn’t himself a prize catch, but the intonation is so beautiful that it may not matter for a while. And in the end, Pierce brings it back to the opening with a direct admission that he doesn’t need the object he addresses:

I tell no lie, I tell the truth

You know I just don’t need to be with you

If I could hold it down

I would sail on through for you

If I weren’t loaded down

I would sail on through for you

There’s no more ambivalence, just resignation. Over the closing, notes, we hear the Morse code found on the cover for the album’s title. Having let go, nothing hurts anymore.

On the original issue of Ladies and Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space, the title track quoted Elvis Presley’s Can’t Help Falling In Love both lyrically and musically. The Presley estate objected and later pressings used a remix of the song without those references, though they’re restored on later pressings still. I mention this because the two-note phrase that opens A Perfect Miracle is also lifted from that song, a little gift for music geeks like yours truly who obviously live for that sort of thing.

The problem, for me, is that by the time I listened the album in its entirety a few years after its release, those first three tracks had turned into background noise. Modern Love barely sounds like a Bowie song at all – the piano and horns driving the sound instead of the guitar, and lyrics that don’t seem to be about anything at all. The live video didn’t give a story to it. Mind you, that’s what was expected of 80s videos and even 35 years later, when I listen to the songs that did have story videos – China Girl and the title track – I still see the videos in my head. And by the time Modern Love was released as the third single in September, we’d spent the summer being bombarded with tracks two and three.

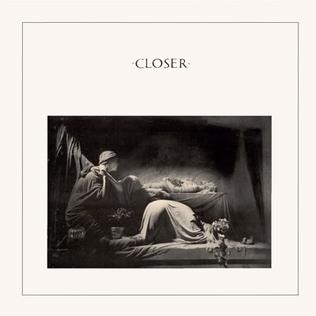

The problem, for me, is that by the time I listened the album in its entirety a few years after its release, those first three tracks had turned into background noise. Modern Love barely sounds like a Bowie song at all – the piano and horns driving the sound instead of the guitar, and lyrics that don’t seem to be about anything at all. The live video didn’t give a story to it. Mind you, that’s what was expected of 80s videos and even 35 years later, when I listen to the songs that did have story videos – China Girl and the title track – I still see the videos in my head. And by the time Modern Love was released as the third single in September, we’d spent the summer being bombarded with tracks two and three. about Closer, and JD in general for me at the time – I knew a little of the history – I’d even seen New Order (the band formed out of the remains of Joy Division) perform. That would have been in

about Closer, and JD in general for me at the time – I knew a little of the history – I’d even seen New Order (the band formed out of the remains of Joy Division) perform. That would have been in  The opening Schizoid man pushes the needle to the red in terms of both saturation and energy. While the structure remains the same, the improvisations in the middle exceed what is expected. Mel Collins’ sax work is intense, and marred somewhat by drumming that seems to be, possibly, part of a different song. Fripp ropes everyone back in with some searing runs. Boz’s treated vocals are more menacing that we hear in later versions, which is somehow appropriate.

The opening Schizoid man pushes the needle to the red in terms of both saturation and energy. While the structure remains the same, the improvisations in the middle exceed what is expected. Mel Collins’ sax work is intense, and marred somewhat by drumming that seems to be, possibly, part of a different song. Fripp ropes everyone back in with some searing runs. Boz’s treated vocals are more menacing that we hear in later versions, which is somehow appropriate. The fascination for Balance in this movie possibly included what was essentially a music video inserted in the midst of Chas’s mushroom trip. When Jagger

The fascination for Balance in this movie possibly included what was essentially a music video inserted in the midst of Chas’s mushroom trip. When Jagger