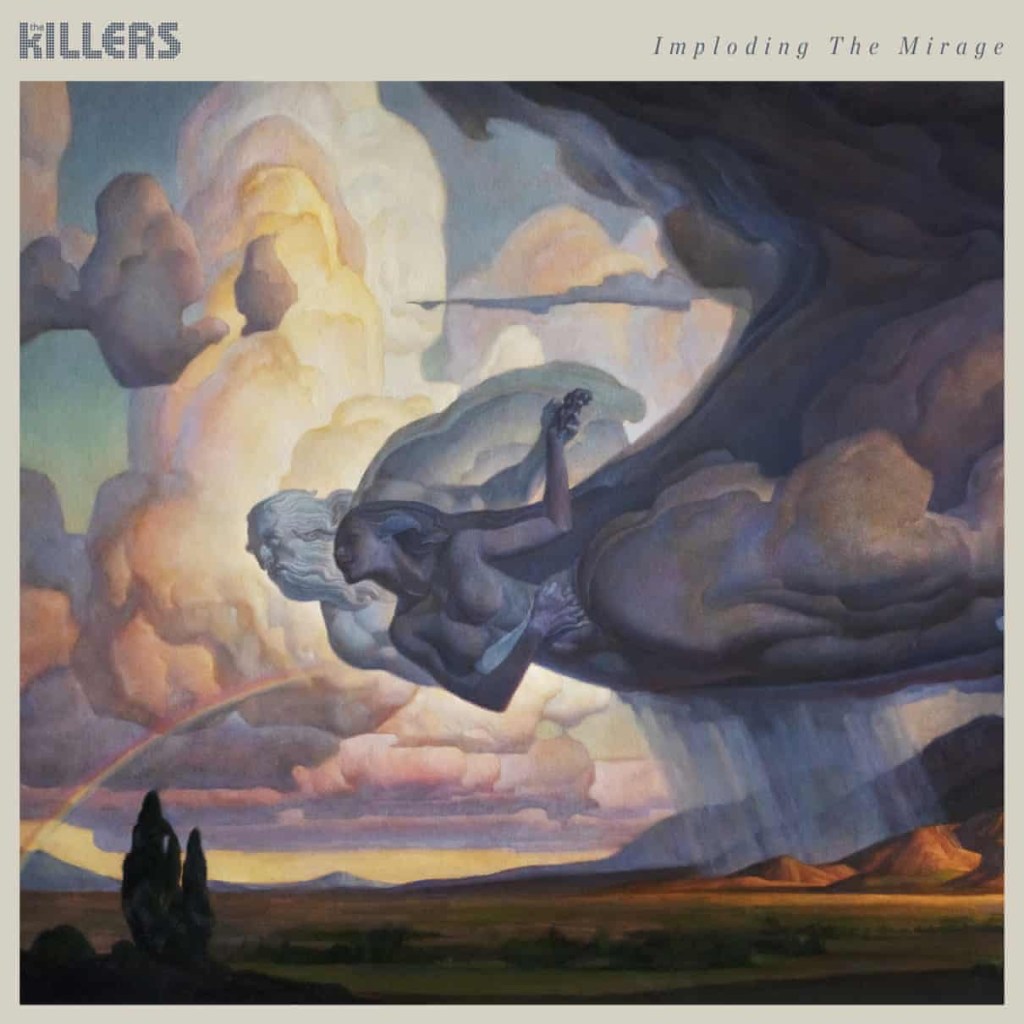

A look at the new albums by The Killers and Chuck Prophet.

These two albums have little in common except that they were released within a couple of weeks of each other.

First up: The Killers’ Imploding the Mirage. Before I heard this album, I’d read Alexis Petridis’ review of it in the Guardian. His main complaint was that the album had the same musical intensity – straight-up intense – all the way through. This feels like a correct assessment, but that’s not really a problem for me. I’ll happily listen to a death metal or stoner rock album straight through and not have a complaint that the thing doesn’t let up. Noting that the album’s title refers to the demolition of a Las Vegas hotel, it’s not as though we weren’t warned about its intentions.

Opening with My Own Soul’s Warning, a piece of pseudo Bruce Springsteeniana that should rope the listener in, we’re left wanting. When Flowers sings ‘something just didn’t feel right,’ I just ask ‘What? What is it? I’m giving you the space to explain yourself and all you can say is “something”?’ I shouldn’t judge my pop singers so harshly, but if you’re going to channel the poetic muse, you have to give it some words to work with.

Blowback uses the term ‘white trash’ to describe its subject, and it’s not the only time Flowers and company do that on this album. It points out how lazy the band (is Flowers the only lyricist?) is at putting words together. Again, I want to like the album, but leaning on clichés like that rather than working out what you mean gets on my nerves. Caution is the other one. It’s the first track I heard off this album when BBC Radio 2 started playing it a couple of months ago. Musically it’s quite inviting, and catchy as hell, but that phrase doesn’t endear me to it. In addition, the chorus refers to both throwing caution to the wind and the winds of change. Come on, already.

Lightning Fields has the benefit of k.d. lang on vocals on a verse and feels like an 80s-era Daniel Lanois production. This isn’t a bad thing at all. It’s followed by Fire In Bone which feels lifted from a mid-80s Bill Nelson album. The band has never shied away from what they owe to the 80s, but it seems rather serious on this track. Also in its favor is not being lyrically embarrassing.

Running Towards A Place is another track that’s musically earnest, by lyrically lazy. The very serious reading of the lines in the chorus make me feel as though Flowers has never read any actual poetry.

Because we’re running towards a place

Where we’ll walk as one

And the sadness of this life

Will be overcome

But someone has shared a bit of poetry with him because he asks in the bridge about worlds in a grain of sand. Of course, that phrase is cliché now as well.

My God is another really intense one. Knowing in advance that Flowers is a Mormon, and that when he addresses God, it’s a rather more personal relationship than what often happens when God shows up in pop music. That said, he’s also lifting, musically, from 80s era Laurie Anderson, an artist who is rarely amorphous when addressing the forces of the universe.

And the album concludes with the title track, which wants to be a declaration of some kind of superiority. While you were doing X and Y, I was doing the serious work of imploding the mirage. But we don’t get the joy of what this means from the voice of someone who can actually describe what makes this important. Instead we get the same dead metaphors and platitudes that this band always relies on, for example,

Sometimes it takes a little bit of courage and doubt

To push your boundaries out beyond your imagining.

Especially in this song which should bring the album to its apex, I feel let down that they couldn’t do better.

It’s a well-produced affair, and well played. Some years back there was a report that Flowers had said in a tweet that he couldn’t sing. I laughed, because I had never given him much credit in the vocals department. Alas, he wasn’t admitting to an overarching personal failing, just explaining a cancelled gig due to laryngitis. One of the nice things about this album is that Flowers does have a voice that he uses well, and that’s instantly identifiable as his. I just wish his poetry was more polished. I don’t even mind how much the band’s (or the producer’s) influences infuse the workings of the thing. I’ve been listening to pop since the 80s, and I pick up on these weird things that might seem minor. On the other hand, the members of Can and Neu! Get writing credits on Dying Breed and for the life of me there’s not much more than a motorik beat to harken back to those 70s krautrock acts. Wikipedia lets us know that there are samples of Neu!’s Hallogallo and Can’s Moonshake in there somewhere. Could be.

And then there’s Chuck Prophet’s The Land That Time Forget.

This isn’t a flawless album, either. But musically, I think Prophet and his band The Mission Express are more interesting. I fully admit to simply liking the kind of music Prophet does more than the polished pop of the Killers. This album is, like a lot of his work, varied in expression, tempo, and subject matter, but holding on to an overarching theme. In this case, the theme has to do with what modern American life inherits from things as disparate as the dance marathons of the 30s and Richard Nixon’s presidency,

High As Johnny Thunders, the first song released from the album, asks what the world would be like if certain things were true, like Johnny Thunders’ first band, the New York Dolls still being together and Romeo and Juliet having kids (‘Shakespeare would be on the dole’). Interesting to think of things like Johnny Thunders still being alive the week that Walter Lure, the last original member of Thunders’ band the Heartbreakers passed away.

Marathon refers to the dance marathons of the 1930s and features the sweet backing vocals and keyboards of Chuck’s wife Stephanie Finch. It’s danceable the way rock and roll was in the 70s. One of the things Prophet’s doing (the hint’s in the title) is playing with how we deal with nostalgia and how our various shared histories play out in the modern echoes. For a day or so people danced until they dropped because it was a way to maybe win an extra prize to live a little like the world wasn’t in the throes of the Depression.

Paying My Respects to the Train slows the action down with some gorgeous lap steel work. Is there a difference between CP singing “I’ve got my heart in my throat and my ears to the track” and some of the overused metaphors found in Killers lyrics? It might be the juxtaposition with the rhyming line “Somehow I know that you’re not coming back” has the recognition that life isn’t moving forward with everyone hand in hand. It’s also an expression of a personal land that time has forgotten.

Willi and Nilli posits a pair living in a ‘Polk Street SRO’ cranking up the stereo and singing ‘Love me like I want to be loved’ till the neighbors call the cops who usually never come. Though come the last verse, the cops all sing along. One thing I love about this song is the fact that only the fact that they live on Polk Street and Willie claims he ‘could make a man bark all night’ indicate that they’re gay as they remember who they were in a different time. Today it’s my favourite song on the album.

Fast Kid tells of a girl who could have come out of one of the songs on Imploding The Mirage.

She’s a fast kid growing up all wrong

Shaking like a leaf in the golden dawn

Gone with the wind, gone with the moon

Gone like the tar in my silver spoon

Is there a difference in his use of cliché? Not sure, but ‘Tar in my silver spoon’, with its heroin reference, brings the song down to the ground and into the alleys where Killers characters never seem to go.

Nixonland posits a trip back in time to San Clemente, the home of Richard Nixon’s California retreat. Prophet uses an electric blues arrangement to discuss what Nixon’s presidency and fall were like. Nixon’s life, and presidency, however aren’t that far from where we are now. He doesn’t draw a direct parallel, but crowds calling Jail to the Chief could have been calling that outside of the White House this year or last or the one just before.

Womankind offers the idea that man does all sorts of things but doesn’t do the things a woman does (‘while they short you every hour for the time that you put in’), and says straight up, ‘They think you’re weak Because you’re soft / I know who’s stronger than me’. Yeah, it’s kind of woke, but it’s the kind of heartfelt admission that woman is more than one archetype or another. It’s possible that Prophet is also putting his female characters on various pedestals – they’re just different than the ones Brandon Flowers uses.

Get Off The Stage, a direct attack on the current president repeats the sincere request that he just leave. Prophet compares his own life with a band (‘in an Econoline van’) with Trump’s (‘You have your crew’). On the world stage, though, Trump is just an embarrassment.

‘You’re an obstruction in democracy’s bowel, and the patient is dying.’ But he suggests, ‘come down and we’ll play some John Prine.’ I love the idea that if he just lets go, we can listen to good music and get on with things, in joy.

It’s not loud or otherwise profane. And it pulls all the history he’s plied on the album into the present day. Is it a suggestion that this too will be a land to be forgotten? None of the stories he tells on the album are of things that are completely forgotten, but that if we’d remember a little harder, we might get over the current obstructions as well. This song contains the album’s only moment of what I consider sloppy songwriting – he suggests Trump is going to prison, ‘but don’t worry, the first time is the hardest.’ The oft repeated suggestion that prison is always accompanied by forced sex doesn’t do anyone any favors, even as Prophet has shown he can write about gay characters without judgement.