Here I look at Lady Day’s final years. She was madly prolific, and along with dozens of classic tracks, recorded two of vocal jazz’s definitive albums: Lady Sings the Blues and Lady in Satin.

Billie’s Blues – Part 1

http://open.spotify.com/user/bishopjoey/playlist/2isTukXm4f9hIU4y6kPGvn

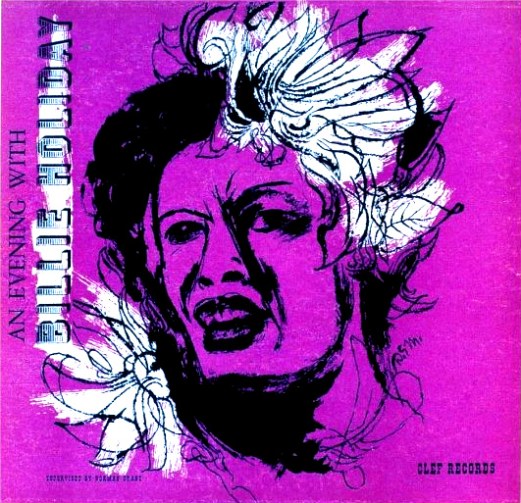

1955 Music for Torching (Clef) /

1956 Velvet Mood (Clef)

Recorded: August 23 & August 25, 1955

Recorded only six months after Stay with Me, you can hear Billie’s voice start to falter in front of this tight combo.

Donald Clarke, in his biography of Lady Day, Wishing on the Moon, (2000) indicates that Billie was in general in a bad way in these years – the 1954 sessions were contentious due to various hangers on and alcohol. The man she was with, a “mafia enforcer” (according to Wikipedia) and pimp named Louis McKay, who took all the money she made and kept her in a state of malnutrition.

This collection very much adheres to the themes of unrequited love suggested by the title, and her phrasing is still pretty tight. On a JATP bill she shared with Ella Fitzgerald during this period, the second half of her set was a bit of a mess – something she blamed on Oscar Peterson (with whom she never worked again), though one guesses it was the drugs. I’m not sure whether this is the show that was released as Live at JATP. In ’54 she cleaned up briefly, but by the end of the year was using again.

Clarke (who isn’t exactly objective in his writing) states that the combo on Music for Torching is “one of the best line-ups Lady ever had.” The subject matter is, as always, love, about equally balanced between requited and not. Come Rain or Come Shine, A Fine Romance, I Get a Kick out of You, and Isn’t This a Lovely Day fall in the first category, though you can hear the longing in them. Isn’t This a Lovely Day, which closes side two, is especially poignant, with her voice playing off the Benny Carter’s alto sex just before a beautiful trumpet solo from Harry “Sweets” Edison.

On the other hand, Gone with the Wind, I Don’t Want to Cry Anymore and I Don’t Stand a Ghost of a Chance With You really point up the album’s title – these are songs about carrying a torch for a love that’s gone. Her phrasing is still the top, but the range is further diminished.

What’s interesting here is the production. Carter and Edison feel far from the microphones, giving the impression she’s singing in an empty room. When the guitar (Barney Kessel again) comes in, and then the piano, they’re much closer, as though replying to the one she’s addressing – the ghost made flesh – in the refrain: “If you’d surrender, just for a kiss or two, you might discover that I’m the lover meant for you, and I’ll be true. But what’s the good of scheming; I know I must be dreaming, for I don’t stand a ghost of a chance with you.” The piano solo (Jimmy Rowles, a graduate of Lester Young, Benny Goodman, and Tommy Dorsey among others, replacing Peterson) might be the reply the singer longs for, but the repeated refrain after the solo returns to the echoing horns.

Velvet Mood leans more towards the melancholy and the arrangements/production put the Billie’s voice more to the front and most of the tracks. The only up-tempo pieces are Please Don’t Talk About Me When I’m Gone (weird, given the lyrical content of the piece, though other arrangements are similarly upbeat) and Nice Work If You Can Get It.

I Gotta Right to Sing the Blues is, in many ways, an extended showcase for Kessel whose solo takes up the middle third of this six-minute track and is almost a blues sermon on its own.

1956 Lady Sings the Blues (Clef)

Recorded: June 6 & 7, 1956, September 3, 1954

Before you read further, listen to Strange Fruit. If you haven’t before, listen carefully. This had been one of Holiday’s signature tunes since its composition in the 1930s. There were times she was forbidden by club owners to sing it.

Around 1998, I took a three or 4-hour drive with a girl who acted and sang in musical theatre and had wide-ranging musical tastes. I had a few tapes in her car, including Live at JATP. At that late date, Strange Fruit still shocked on first listen.

That said, this album was my intro to Lady Day. I bought a Japanese cassette of it in 1986 and it spent a lot of time in my tape player. I’m not sure who recommended it to me – it’s nothing like anything I was listening to at the time, but from Chalie Shaver’s opening trumpet blast on the title track, I was hooked.

For this album, Holiday re-recorded eight earlier hits and four new songs (the title track, Too Marvelous for Words, Willow Weep for Me, and I Thought About You) to coincide with the release of her ghost-written autobiography. The arrangements reflect those of the earlier Clef albums. Songs of love and loss are punctuated by God Bless The Child, (for which, like the title track, Holiday shares a writing credit) about the importance of self-reliance, and Strange Fruit. Strange Fruit, an absolutely chilling song about lynching in the South, had been in Holiday’s repertoire since its composition in the late 1930s. The song and its writer, Abel Meeropol, have a very interesting history. A socialist, Meeropol later adopted the children of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg who were executed for passing nuclear secrets to the Soviets at the start of the Cold War. You can find a brief history of the song (and a long digression on the connections between Stalinism and the US Democratic party) here.

In terms of the arrangement of the album and the arrangements of the songs, it’s always struck me that the title track and Strange Fruit have these crazy trumpet blasts. Donald Clarke complains “the only studio recording of ‘Lady Sings the Blues’ has an introduction and a finish with a drum-roll and open trumpet, sounding like bullfight music. ‘Strange Fruit’ also gets open horn, and for once Shavers indeed sounds overbearing, partly because of the recording quality.”

Despite having been recorded in three different sessions (tracks 1-8 being the July, 1958 dates in New York, 9-12 coming from 1954 dates in California with no overlapping players), it comes off to me as being a unified whole. Again, this was my intro to her and I’d never heard anything like it. Critical dismissal of this or that aspect of it doesn’t really hit me. These are the versions I know best – earlier recordings, even though she’s in better voice, don’t sound as good to my ear.

1957 Songs for Distingué Lovers (Verve)

Recorded: January 3, 4, 7, & 8, 1957

Originally only six tracks, all from what’s become known as the American Songbook. The album includes one Rogers/Hart, two Johnny Mercers, a Gershwin brothers, and a Porter, rounded out by the Parrish/Perkins composition Stars Fell on Alabama. It continues the small group work she’d been doing in the 50s on Verve. The group includes several who are on the earlier sessions including Edison Webster, Kessel, and Red Mitchell.

And as had been usual at this point, the voices of the musicians seem to outshine Holiday’s own declining vocal talents, but again, her phrasing is still impeccable. She and Webster almost have a duet going on Mercer/Allen’s One For My Baby (And One More for the Road), a song that Frank Sinatra recorded for three different albums in the 50s, notably Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely the following year. (His 1947 version is much more upbeat, while the ’58 is much closer to Billie’s.)

I think this late version of Porter’s Just One of Those Things feels a little forced vocally, but it has several fantastic solos. Kessel, Edison, and Webster each provide beautiful solos that flow with the seemingly effortless playing they always displayed.

The closing I Didn’t Know What Time It Was has the vocal regret the lyrics seem to demand, when she sings “Yes I’m wise and I know what time it is now,” it’s sounds clear that she does.

1958 All or Nothing at All (Verve)

1958 All or Nothing at All (Verve)

Recorded: August 14 & 18, 1956, January 3, 7, & 8, 1957

From the same sessions that produced Songs for Distingué Lovers, you can hear the same diminishing voice, but excellent phrasing and the accompaniment is spot on. There’s not much to distinguish these last two albums from one another – it’s mostly a matter, I’m guessing, of what Verve chose to release. I don’t know if she was at the end of her contract (much as Miles was with Prestige) and met her obligations by letting them take what was useful from the sessions. In keeping with the album’s title, the songs alternate between those that deal in love and those that suggest love’s ending.

Weill and Nash’s Speak Low seems prescient, “Love is pure gold and time a thief / We’re late, darling, we’re late / The curtain descends, ev’rything ends too soon, too soon” and she handles it with the sadness and resignation the song demands.

Another interesting item is I Wished on the Moon, an unlikely song of requited love both because Billie seems rarely sang any so straight up romantic as this one, and because its lyricist, Dorothy Parker, was known for her caustic wit. (Compare the lyrics to I Wished on the Moon to Parker’s poem One Perfect Rose.)

Well, the romance doesn’t last long. I Wished on the Moon is followed by the Gershwin’s But Not For Me, in an upbeat, swinging arrangement. The fact remains, that this one is about the love others seem to have that the singer does not.

Berlin’s Say It Isn’t So begins with only Jimmy Rowles’ sparse piano for accompaniment. At the bridge Edison and Alvin Stoller join on trumpet and lightly brushed drums. Webster’s saxophone comes in for the final verse, bringing the mood up a little, but the retaining the song’s air of despair. Finally, the Gershwins’ Our Love Is Here to Stay brings the All back.

1958 Lady in Satin (Columbia)

Recorded: February 19, 20, & 21, 1958

Lady Day’s final album was in fact the first of her music I heard. Either my mother or my sister bought the album in ’81 or so. I wasn’t sure what to make of Ray Ellis’ orchestral arrangements. I first heard these songs before Linda Ronstadt brought fully orchestrated music back to the top 40 with her Nelson Riddle collaborations (What’s New, 1983; Lush Life, 1984; For Sentimental Reasons, 1986), and was mostly listening to rock and new wave at the time anyway.

On a certain level, one can accept the Penguin Guide’s comment that this album is “a voyeuristic look at a beaten woman,” but that’s rather unfair. Despite the complete loss of her upper range, the production keeps her vocals at the forefront of the music. Unlike the small sessions on Verve, the orchestra often act as more of a wall of sound behind the voice.

Hoagy Carmichael’s I Get Along Without You Very Well is oddly well served by its slightly broken vocals. I’ve forgotten you just like I should / What a fool am I to think my breaking heart could kid the moon.

For me, the standout track is Violets for Your Furs. The simple bass line carries Holiday’s voice though distant violin blizzards. The bridge features a beautiful interplay of strings and trombone (there are four on the album – not sure who plays that section) that evoke the winter day blue sky that she sings of.

It seems there were initially two editions of the album – the stereo version had eleven tracks and closed with I’ll Be Around. The mono version closed with The End of a Love Affair. The narrator of I’ll Be Around carries the same lyrical torch as that of I Get Along Without You Very Well – one that indicates, you know when you’re done with that floozy who’s caught your eye, I’ll still be there. It fits with the album, but it’s an odd note to close on.

The End of a Love Affair (which oddly has a stereo mix which is available on a 1997 reissue) seems to be tacked on as well. It’s a beautiful evocation of what the jilted lover feels. The instrumentalists are more the spotlight of the song as well, almost overpowering the vocals. The combination of songs and arrangements is wonderful, but when it came time to put the album together, the producers didn’t quite know what to do. But Beautiful or For All We Know might have been better choices, but they didn’t have me to make the perfect track listing.

After Lady In Satin, Holiday, Ellis, and a smaller group (fewer strings, no choir, but Harry Edison in the group) convened for sessions on which she said she wanted “to sound like Sinatra.” The recordings were completed in March, 1959. In July, her excesses took their final toll and she died at the age of 44. MGM released the album with the title Last Recordings, but I think they were just cashing in. It certainly swings with songs that she might have done justice to earlier in her career, but her voice is positively shot. It’s not so fitting a coda to her career as theprevious, but she takes chances with the selection. While You Took Advantage of Me and Baby Won’t You Please Come Home come off as a little bit embarrassing, Just One More Chance is really quite poignant, and All the Way showcases her phrasing and style. Alas, Ellis himself took over the production tasks and didn’t have the chops that Irving Townshend brought to Lady In Satin.

e Holiday

e Holiday